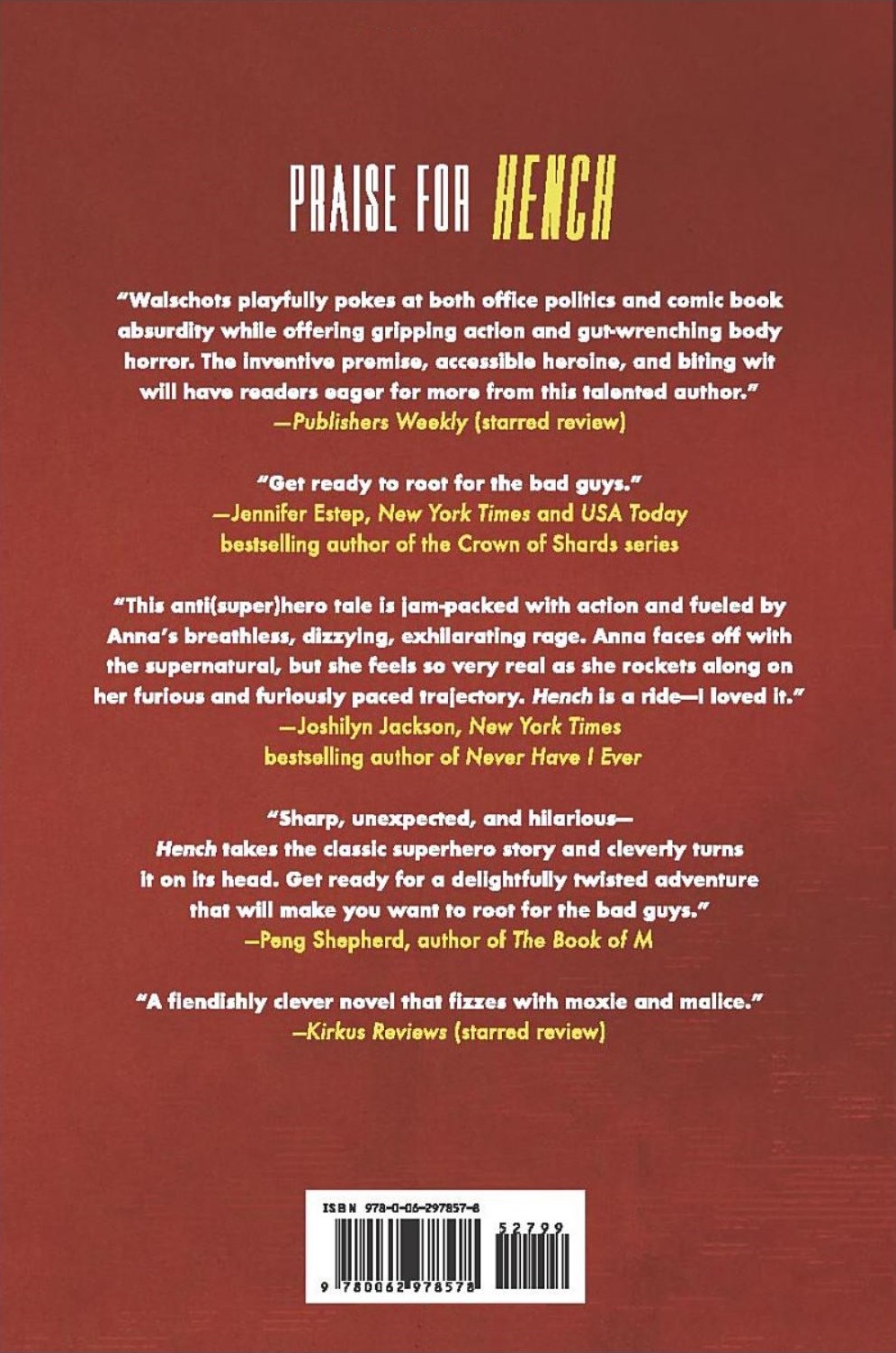

Until this moment, Hench is funny, full of a matter-of-fact, affectionate despair at everyday economic hardship. Have you ever wondered what happens to bystanders during those epic, glorious superhero fights we see in (insert superhero franchise here)? Hench tells you, and it doesn't pull its punches. (The villain wants to make sure there's a woman standing up with the rest of his goons.) (The gig economy sucks.) Anna is our delightfully acerbic protagonist, hired by a middling supervillain to do data entry at his start-up, until one day she finds herself center stage during a villainous press conference. Henches who survive a supervillain-foiling find themselves back at the Temp Agency, struggling to stretch that last paycheck until the next no-benefits, probably-short term job. Turnover is high and contracts often end abruptly, as superheroes with an array of impossible powers are very much also active.

In the world of Hench, people willing to work ("hench") for supervillains go to an employment agency. It's smart and imaginative an exemplary rise-of-darkness story, one I won't soon forget. Hench is an engrossing take on the superheroic. We might be less familiar with how to estimate lifeyears lost, but be assured (note, I don't write reassured) there is a method to calculate that loss, too.Īnd in Natalie Zina Walschots' debut novel Hench, she examines what happens when the ability to calculate the human cost of disaster is coupled with a superhuman ability to organize and manipulate data. They are blazoned across every story, destroyed property valued to the last cent. In 2020, we are familiar with the economic costs of natural disasters.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)